Sleeping Beast: The Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Plant

It was an overcast, dreary day in early spring. The snow had just melted, but the wind still bit at my knuckles as I cut through a chain link fence and clambered down a hill onto the train tracks. Waving to a passing conductor, I turned to my left and was met with what would come to be one of my favorite sights in Philadelphia. A single smokestack, only the top of which was visible over the embankment of tall grasses that surrounded the railway. Walking the half mile along the tracks and under the streets of Allegheny West, a massive factory facade of brick and broken windows revealed itself. Massive blue banners draped the building, illustrating plans for its future that seem distant and unrealistic. The walls only seem to expand as you approach, until the tracks split the factory in two. On my right stood an old wooden ladder, and at the top stood a door; open then, today welded shut. This wasn’t only the doorway to a factory I would grow to love, but a doorway into a world of history I would’ve never explored.

When I first visited Budd in March of 2025, I had no idea what to expect. I’d always been drawn to places void of people, forgotten; asylums, churches, apartments, schools. But stepping foot into Budd for the first time was something different. Climbing that ladder and stepping inside the factory, you’re immediately plunged into a cold darkness, with a smell of lead paint, decay, and old water any urban explorer would recognize. The floors are caked in dust from the paint, chipping off the concrete walls and crunching under my boots with every step. The entrance is small; a long hallway, a couple turns, and as you make your way through, the space starts to open up. As you turn another corner, pitch black turns into a flood of light.

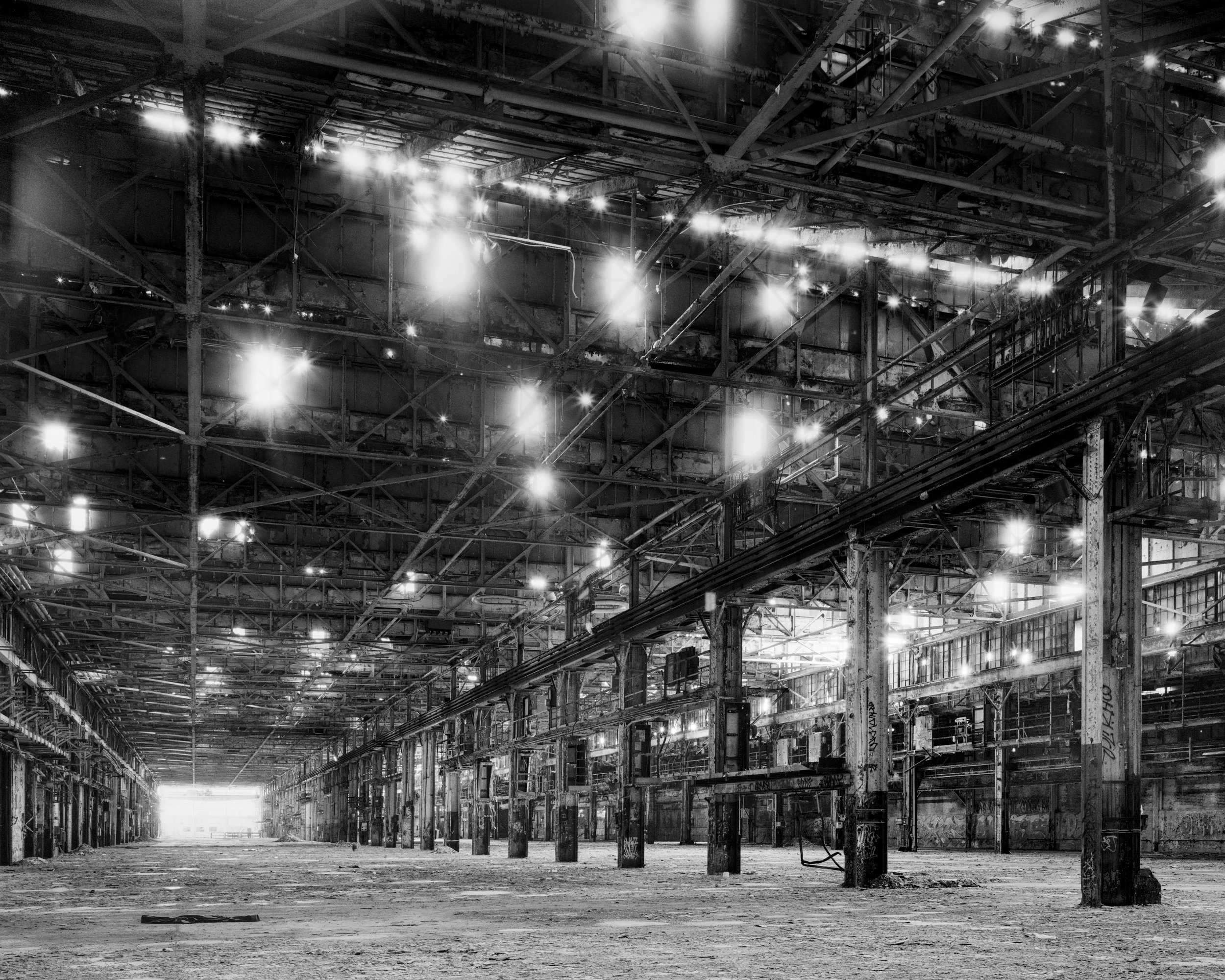

One of the most defining features about the factory is its massive, open indoor spaces. The Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Plant was known for its pioneering innovations in the automotive, train, and aviation industries, and although it’s now empty, it’s easy to see how this was a powerhouse in the American manufacturing industry throughout the 20th century. The Zephyr building in particular, which sits along the tracks parallel to Fox Street, boasts 50-foot ceilings above a room that spans over 3 football fields long and totals at over 235,000 square feet alone. The building was birthplace of the revolutionary Pioneer Zephyr, a sleek, modern, stainless-steel train that used a new diesel electric engine which quickly set records and replaced steam locomotives. One such notable record was the "Dawn-to-Dusk" run, a publicity stunt ride in 1934 that peaked at 112 MPH and completed a journey from Denver to Chicago in only 13 hours. Inside Zephyr, you can still see original signage, 5-ton bridge cranes, and small intact switchboards attached to the many of the supporting columns.

On the flipside, Budd has a massive maze of smaller floors interlinked throughout multiple buildings, focused on smaller parts of the assembly line, like individual parts or metal stamping for automobile bodies. A conveyor line runs along the ceiling of many of these smaller rooms, so workers could receive a part, do their work on it, and send it down the line without moving too much from their station. These areas are repetitive in their architectural nature, all including long rows of either cylindrical or rectangular concrete structural columns. Without your bearings, it’s extremely easy to get lost in these rooms as there’s almost no points of reference except the windows and graffiti. Most of these floors are stacked upon each other in their own buildings, with certain floors linked to the other parts of the factory via hallways or flyovers.

The outside of the factory, although its metal rusted, windows smashed, and brick chipping away, is nothing other than beautiful. The factory buildings include a string course, featuring a geometric diamond design of white and red brick which wraps around the top of every multi-story building at Budd. The factory started as a single building in 1915, and throughout the years, more additions were created to accommodate the growing manufacturing needs of the company. This gives a visibly patchwork-style feeling to the exterior, one that doesn’t come at the detriment of attractiveness but rather adds to it. From the street, the grid of the building’s former windows looms overhead, requiring a strain of the neck to see the top. The roof offers a great view of the Philadelphia skyline, and Budd sunsets are some of the best I’ve ever witnessed.

Not only is it beautiful, but Budd has an incredibly rich history. Edward Gowen Budd began his career after high school at Hale & Kilburn in Philadelphia, where he helped perfect the arc-welding process and created the first all-steel railcar prototype. In 1909, after Detroit firms refused the challenge, Budd was approached to design an all-steel automobile body. He succeeded, producing bodies that were shipped by rail to Detroit and assembled into the Hupmobile 32. When Hale & Kilburn was purchased by J.P. Morgan in 1911, Budd lost the freedom to experiment that had defined his work. After a mental breakdown and brief departure to Europe, he resigned, determined to work on his own terms.

On July 22, 1912, Budd founded the Edward G. Budd Manufacturing Company using $75,000 of his own money and $25,000 from investors. After years of instability and near bankruptcy, the company secured enough contracts to settle permanently in Allegheny West, Philadelphia. There, the factory rapidly expanded, employing thousands and growing into a massive industrial campus. By the late 1910s, the plant featured tens of thousands of windows and offered amenities uncommon for industrial workplaces at the time, including a cafeteria, company orchestra, newsletter, sports teams, and an in-house physician. During World War I, Budd was called to help the war effort, and notably produced over one million steel helmets before the contract was canceled.

The Great Depression hit the company hard, forcing layoffs that Budd viewed as personal failures rather than financial necessities. Despite economic strain, innovation continued, particularly with the early adoption of stainless steel as a structural material. Budd’s experiments in aviation were technologically impressive, even if commercially unsuccessful, and further reinforced the company’s reputation for engineering ambition. These innovations laid the groundwork for Budd’s lasting impact on transportation manufacturing beyond the factory walls.

During World War II, production shifted entirely toward the war effort. As men left to fight, women filled the factory floors, at times comprising the overwhelming majority of the workforce. The Philadelphia plant became a major producer of military equipment, including the vast majority of anti-tank M1 rockets, as well as aircraft components, vehicle parts, and artillery shells of all sizes. When the war ended, Budd himself personally delivered a speech promising every single returning veteran employment, regardless of injury or trauma. Especially regarding PTSD, this was something unheard of at the time. Major postwar investments modernized the plant, expanding storage capacity and upgrading machinery. Sadly, Edward G. Budd passed away in 1946, shortly after seeing the company return to peacetime production.

After Budd’s death, the company continued to diversify, supplying components for nearly every major American automobile manufacturer and expanding into defense, testing equipment, plastics, radiography, and even nuclear research. By the mid-20th century, Budd reached record manufacturing levels, producing 8 million cars in 1955 alone, standing as a symbol of American industrial power. However, foreign competition, ownership changes, and the decline of domestic manufacturing in the late 20th century began to erode profitability. Plants closed, divisions were sold off and demolished, and operations slowly withered away.

The Philadelphia rail division survived longer than most, continuing production until the late 1980s. Brief revivals and new ownership extended the life of the Hunting Park Plant into the early 2000s, but sustained losses ultimately sealed its fate. By the end of 2003, the final employee had left the factory. Since then, portions of the property have been sold and repurposed, but the main complex remains abandoned, where it is today. After security contracts were terminated, scrappers tore out almost anything of value, including most of the electrical wiring and plumbing. One such scrapping operation ended tragically in 2012, when a man was shot and killed in a gunfight over a truckload of copper. His partner attempted to flee but was quickly apprehended by police. Today, with nothing left to steal, Budd is almost always vacant, only home to a few photographers, graffiti artists and explorers.

This project I shot on 4x5 film is the epitome of all the work I’ve put in inside this factory, the countless hours over 26 separate trips, the ups, the downs, and everything in between. I know this place like the back of my hand. In all the time I’ve spent here, I’ve given tours and taught the history of this factory to more people than I can remember, shot it on 5 different cameras, ruined multiple pairs of jeans, and I can’t wait to get back out there. To me, the Budd Factory is a sleeping beast. What was once a roaring, proud symbol of American manufacturing is now eerily silent. Only the whine of creaking sheet metal, droplets of water hitting puddles on the floor, gusts of howling wind and very occasionally, the faint click of a shutter, remain. The bones of this factory, the concrete columns, the steel beams, from the pulleys on the ceiling to the dust on the floor, tell a story I could never do justice. While Budd’s future remains uncertain, there’s one thing I’m sure of; its history will endure until its heart beats again.

A Truck with its Creator, Zephyr Building

Hunting Park Plant Interior Facade, Press Room Roof

Hunting Park Plant Facade from Hunting Park Avenue

Removed Budd Company Logo

Hunting Park Plant from Salvation Army Soccer Field

Tracks along the Zephyr Building, Former water tower

Hunting Park Plant left, Zephyr Building right

Only Entrance, Zephyr Building Facade

Flood of Light, Shock Room, Hunting Park Plant

Electrical Meters, Loading Station

Columns, Zephyr Building Interior

Main Hall, Zephyr Building Interior

Switchgear Cabinets, Zephyr Building

Former workshop, Hunting Park Plant

Budd Sunset